By Brad Sewell on August 12, 2014 at 11:00am

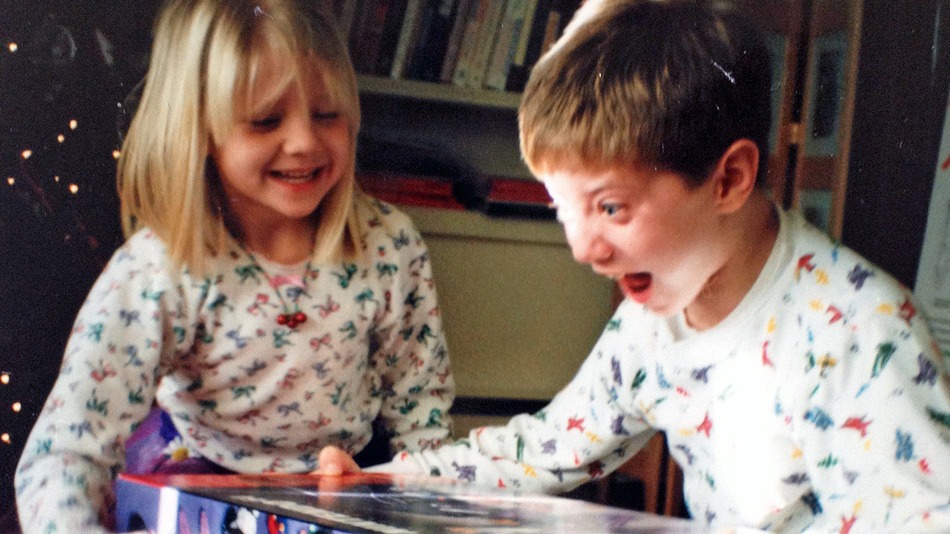

As gamers, we’re familiar with the struggle between those for and against our community and lifestyle. Those who support tout that games improve cognition, reasoning, and nonlinear thinking methods. The opponents counter with studies that claim gaming increases chances for aggression, depression, or simply that they might become mother’s basement shut-ins. Often at the focus of the disagreement is childhood and adolescent development and whether or not childhood gamers develop the social skills that they’ll need later in life. How much should children and young teens be allowed to play, and how much is too much?

Dr. Andrew Przybylski of the University of Oxford researched this case, sampling nearly 5,000 children from the UK aged 10 to 15. In the opening statements of his paper, Przybylski stated that he sought to be open to both the positive and negative effects of gaming, and the study largely reflects his balanced approach.

The surveyed children ranked their amount of time spent gaming into four different categories: not at all, less than one hour per day, between one and three hours, and more than three hours. The survey originally included an option for those who played more than seven hours, but those were merged to the category for lower than three hours as less than 2 percent of children qualified. They were then surveyed on overall life satisfaction across five categories - school, school work, appearance, family, and friends.

The initial finding was that children who played for an hour or less per day actually did show increased life satisfaction over their non-gaming counterparts. Przybylski points out that light gamers “showed higher levels of prosocial behavior and life satisfaction and lower levels of internalizing and externalizing problems.” They were able to reap the benefits of playing video games without devoting so much time to it that they crowded out time that could be spent for adolescent development.

The rising slope was a short one, though. Those who played between one and three hours showed negligible differences in life satisfaction compared to those who did not play at all. Although those gamers were still benefiting in some way to at least not fall behind on their development, they were spending one-third to one-half of their otherwise free time with games.

The three-hour mark is where gaming became a burden on the children. According to Przyblyski, heavy gamers were a “mirror image” of light gamers, showing lower levels of life satisfaction and increased chances of internalizing and externalizing problems as more than half their free time was spent on one activity.

What does it all mean? It means that those who play moderately are not really any better or worse off than those who don’t play at all, but both of those groups could improve with some gaming. The real danger is in devoting so much time to video games that they pull children away from their normal lives - although much the same could be said for any obsessive activity.

Many of us are prone to a Saturday afternoon “Skyrim” binge - which is hopefully fine in moderation - but we could stand to unplug a little more often, get some real human interaction in, and go out in the sunlight. Unless that’s already all that you do, in which case you should probably pull up a seat and race a few laps in “Mario Kart.”

Pediatrics